The twentieth century was an important time for music all around the world. From the rise of jazz in the early half of the century to the advent of rock and roll in the 1950s and the subsequent musical revolution that followed it worldwide, the importance of music grew immeasurably, to the point where, in order to properly control your population, you needed to control what music they were listening to. This censorship of music can be seen during Franco’s regime in Spain from 1939 to 1975, with the government’s position changing in each phase of the era.

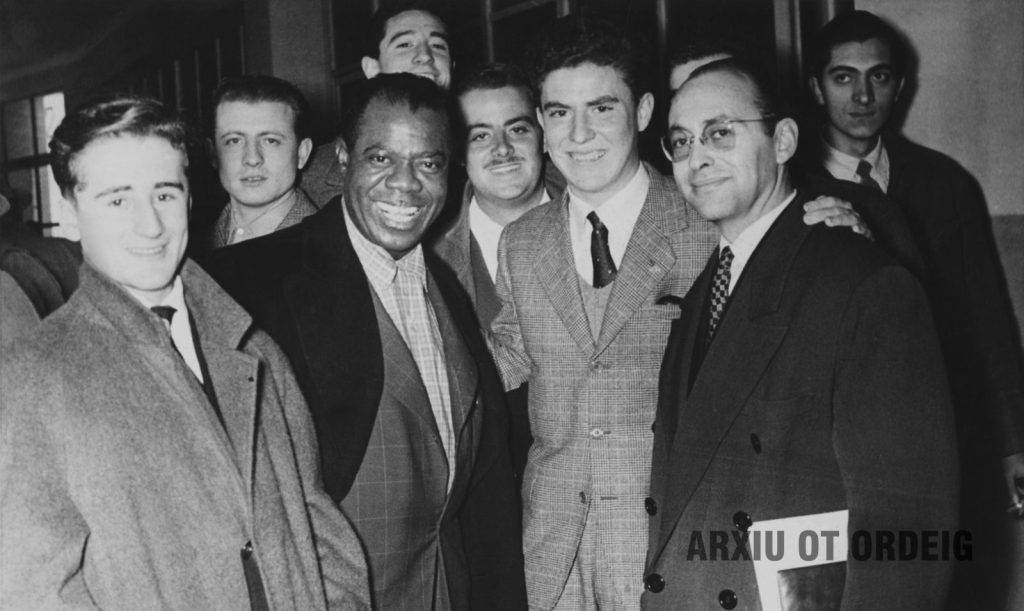

There is a huge difference between the regime’s attitudes to music in the first stage of Francoism (1939-1957) and the second (1957-1975). During the first, rock music was not particularly vilified or persecuted; Franco’s government was more focused on jazz. Before the Spanish Civil War, jazz became popular throughout Spain due to American groups performing in large cities like Barcelona, Madrid, and San Sebastián in the late 1920s. The first jazz club was opened in Barcelona in 1934.

However, after the end of the war, in the early forties, this genre of music began to be suppressed. The Falangist Vice-Secretariat of Popular Education banned the broadcasting of ‘so-called black music, swing dances, or any other kind of compositions whose lyrics are in a foreign language, can erode public moral or the most elementary good taste’. A key part of Franco’s ideology was the ‘Hispanization’ of Spain, which aimed to get rid of external, western influences (such as jazz) and replace them with Spanish traditions like folk songs. Because of this censorship, many jazz clubs closed and musicians left the country.

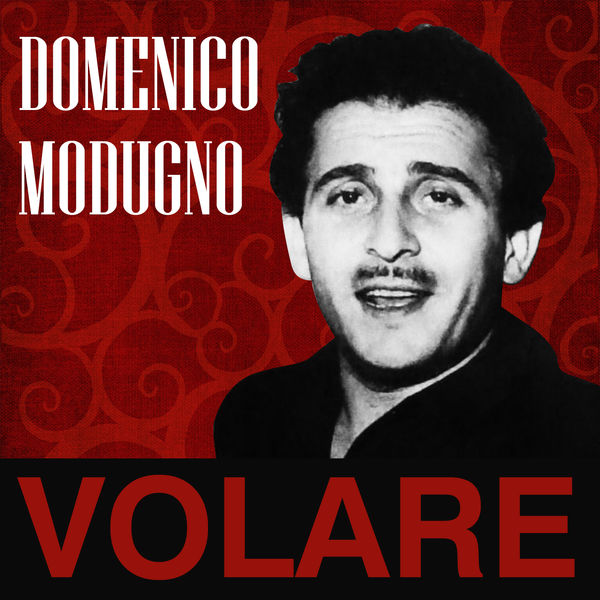

Contrary to the persecution and suppression of jazz, Franco’s government was rather indifferent to rock music during the first stage of the regime, apart from a few album cover changes and some vetoed song releases. This was mainly because there was a relatively small number of people who could understand foreign music with lyrics in English or French, but also because the primary rock influences in the 1950s came from Italy and France, not the UK or USA. The regime viewed rock solely as a musical movement, seeing no reason for concern.

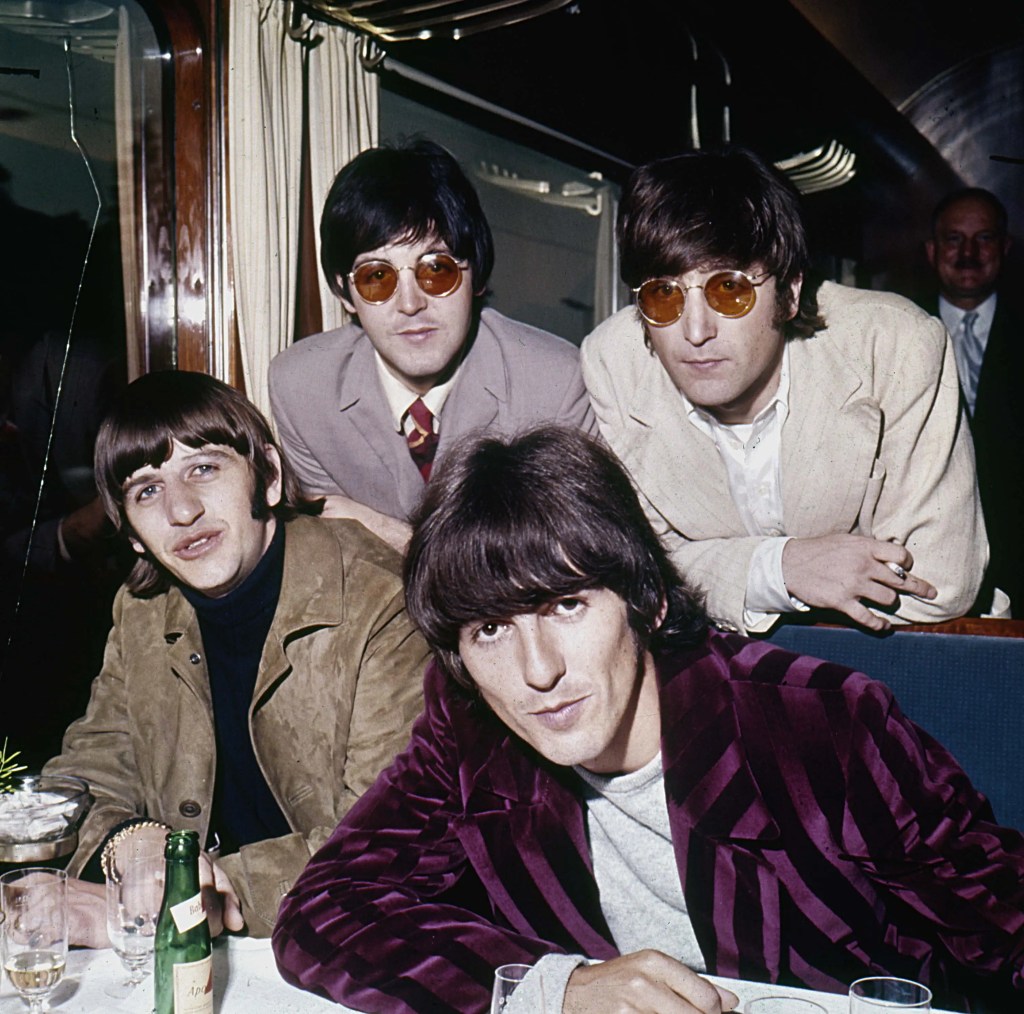

This attitude changed completely in the early 1960s due to a phenomenon known as British Invasion. Beginning with the success of the Beatles, British music was beginning to take over, not just in the UK, but throughout the world. The emerging British rock styles spread quickly, transforming the landscape of rock ‘n’ roll. They sparked the formation of numerous bands and youth movements across all continents, and Spain was no exception. With these new Anglo-Saxon influences, new bands and solo artists began to appear up and down the country, such as Miguel Ríos, Los Pekenikes, and Los Sonor, among many others.

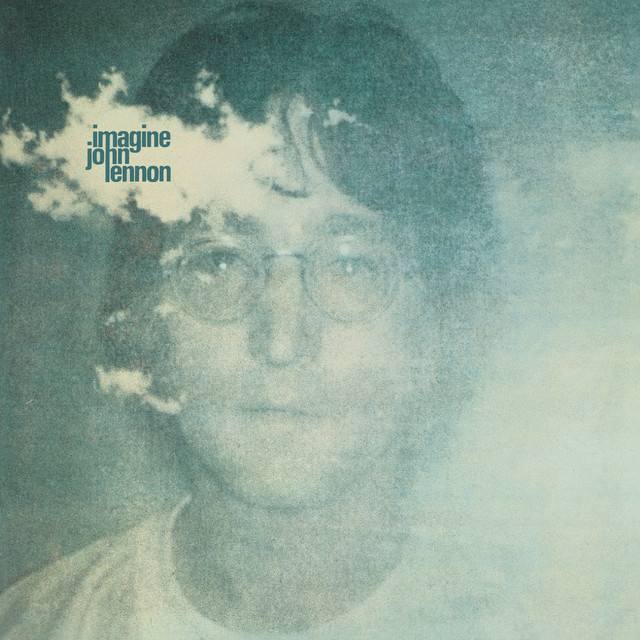

As a response to this, Franco decided to promote the national product by helping musicians who were pro-regime and sang in Spanish, and attempting to get rid of foreign influences. In addition to this, many songs and albums were partially censored, modified, or banned altogether because they were deemed subversive. This includes songs like John Lennon’s Imagine, the song which became a peace anthem of sorts after its release in 1971, was banned on the grounds of being a “song completely negative, removes everything, including religion, hoping that eventually all will join in with the idea”, and Lennon’s Power To The People, deemed “highly subversive”.

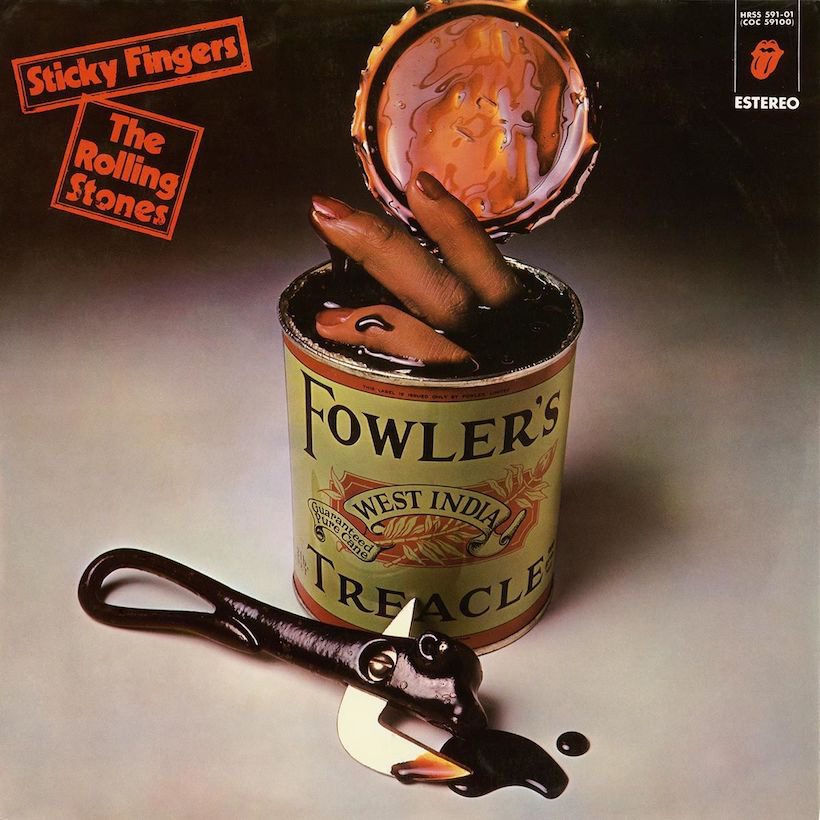

Another reason why songs were banned is if they were in any way contrary to the state’s official ideology. Graham Nash’s Military Madness was regarded as ‘antimilitarist’, which of course went against Franco’s military dictatorship. Elton John’s Tiny Dancer was also censored on the grounds of containing “disrespectful phrases”, referencing mentions of catholicism in the lyrics. The album cover for Sticky Fingers by The Rolling Stones, released in 1971, was changed, and Sister Morphine, a song on that same album, was replaced for containing references to drugs. Finally, John Mayall’s song Mr Censor Man was banned because it was “attacking censorship … It is improper for Spain anyway”. In criticising censorship, it was essentially going against an element of Francoist ideology.

Censorship was a cornerstone of Franco’s regime, and the government’s relationship with music is a clear example of it. Clearly understanding the potential that music has to move and influence people, Franco made sure that whatever was allowed aligned with his official state ideology. This is why western foreign influences, as seen particularly in jazz and rock and roll, were tightly regulated, and any songs that contained references to things outside of what was deemed appropriate during the Francoist regime were censored or modified. By keeping out songs of a particularly subversive nature, Franco was able to keep his control over the Spanish population and fully enforce his conservative ideology.

Leave a comment